Reflections on Children’s Music – Part VI – Ella Jenkins

10 Friday Aug 2012

Written by Gary Storm in Songs for Children

Tags

Dante, Ella Jenkins, Leslie Fiedler, Robinson Crusoe, Thoreau, Virgil, You’ll Sing a Song and I’ll Sing a Song

Share it

(I introduced the great American scholar, Leslie Fiedler, in Part I of these essays on children’s music. My comments are informed by concepts introduced in a graduate course Leslie taught on children’s literature.)

(I introduced the great American scholar, Leslie Fiedler, in Part I of these essays on children’s music. My comments are informed by concepts introduced in a graduate course Leslie taught on children’s literature.)

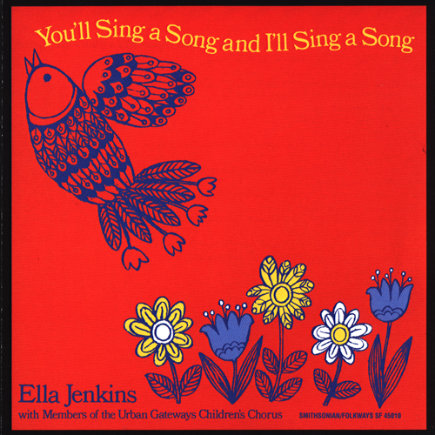

Ella Jenkins is one of the most active and joyful of all children’s folk musicians. You can tell, just from listening to her voice that she is both tough and lovable. You can have fun with Ella, but you don’t dare misbehave. And there is a true scholarly spirit behind her prolific collecting and recording of children’s folk music from around the world. We are listening to a call and response song, a song style that appears frequently on Ella’s records. She brings the whole audience into her songs, makes each child a participant in her performance. This album was recorded with children singers – as the album cover says, “Members of the Urban Gateways Children’s Chorus” – and they reply to each of her questions.

Did you feed my cow? (Yes, Ma-am)

Could you tell me how? (Yes, Ma-am)

What did you feed her? (Corn and Hay) . . . .

And so the story goes until:

Did my cow get sick? (Yes, Ma-am)

Was she covered with tick? (Yes, Ma-am)

How did she die? (Uh, Uh, Uh)

And then, a rather doleful end:

Did the buzzards come? (Yes, Ma-am)

How did they come? (Flop, Flop, Flop)

Here is another children’s song that doesn’t feel bleak, until you explore its logical implications. The loss of a cow to a small farmer was often not merely a sad event, it could be financially devastating. Another wrinkle: cows are ruminants and they cannot digest corn. Did her diet contribute to her demise?

Leslie Fiedler said that kids don’t need a happy ending. Children’s literature, and I would add, children’s music, does not do away with despair. These art forms celebrate, explore, and elucidate sadness, loneliness, and terror.

Books chosen by kids are about terrible situations, not benign ones. Children respond to books about horrifying psychological states. For example, even though it was not written for children, they chose Robinson Crusoe because its essential appeal is terror. The subtexts of the book are fear of injury, fear of starvation, and fear of cannibalism.

Leslie said despair is celebrated in the happy endings and despair is celebrated in the sad endings. This is an aphoristic way of saying that children understand and are fascinated by bereavement, isolation, danger, alienation, fear. They live with nightmares. Children love, in fact, need stories that deal with and resolve these fears. They love going through a nightmare with someone.

And that is the astonishing thing about this song. When you hear it, when you sing it with your kids, when you laugh about it, you have no sense of its true subject matter. Until you somehow separate yourself, and objectively reflect upon the lyrics, do you realize how grim and smelly and sad and repulsive they are. And this is the most powerful magic of children’s music. It allows us to bluntly reflect upon the inescapable horrors of life – without feeling the horror. Children’s songs are like benign Virgils taking diminutive Dantes by the hand, and guiding them, protectively, through their nightmares.

Leslie asked, what is at the heart of a book that moves any person? And he answered, great books allow us, in a state of waking consciousness, to explore the deepest psychological forces by which we are driven. “Did You Feed My Cow?” does this by exploring the over and over great circle of nourishment, life, death, and the return to nourishment. This is what Thoreau meant when he stated, “Our truest life is when we are in dreams awake.” The best children’s stories – and children’s songs – do this.

Traditional, Music by Ella Jenkins, “Did You Feed My Cow?” Ell-Bern Publishing (ASCAP) (1966). From Ella Jenkins with Members of the Urban Gateways Children’s Chorus, You’ll Sing a Song and I’ll Sing a Song, Folkways Records, FC 7664 (1966). Album design – June Martin, Ann Erickson; Illustration – Yoko Mitsuhashi.

Henry David Thoreau, “A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers” (Published 1849). From Henry David Thoreau. A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers; Walden, or, Life in the Woods; The Maine Woods; Cape Cod (Ed. Sayre, Robert F. Sayre). New York: Library of America (1985), page 243.